Army paratrooper Howard "Kobie" Johnson was in a convoy to Baghdad on June 9 when bullets ripped through the skin, muscle and bones of his left arm.

|

Karen Quincy Loberg / Star staff

During his first full day home on leave, Army Spc. Howard "Kobie" Johnson of Newbury Park watch his brother's football practice at Thousand Oaks High School with girlfriend Elena Masara of Vicenza, Italy. Johnson was shot during a mission in Iraq in June. |

|

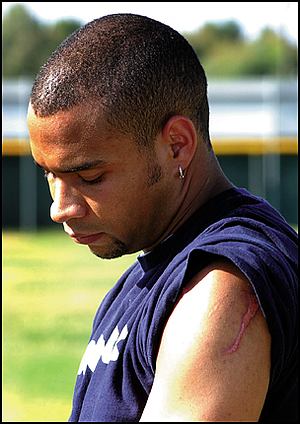

Karen Quincy Loberg / Star staff

The wounds Army paratrooper Howard "Kobie" Johnson acquired on June 9 in Iraq are still visible on his shoulder as he shows them to his stepmother while home on leave. |

His arm limp, bones protruding from the wrist, Johnson picked up his M-4 machine gun with his right hand and fired back. Johnson continued shooting until everyone had gotten out of his Humvee, putting down his gun only to pull a soldier shot in the face to safety.

Two weeks later, Spc. Johnson, 30, of Newbury Park was in a Washington, D.C., hospital. As he went through surgery after surgery and learned to use his hand again, he was told he wouldn't get a Purple Heart medal.

Johnson figured it was because of confusion over whether he was shot by Iraqis or American soldiers when his convoy got caught in a crossfire. Both types of bullets were found in his Humvee, he said.

When Johnson arrived home last week for a visit, he was still bewildered and frustrated.

"I don't want for the whole thing I accomplished over there to be erased and forgotten," the Newbury Park High School graduate said as he watched his younger brother practice football at Thousand Oaks High School.

But Friday morning over the breakfast table, Johnson's resentment dissolved as his father, Howard F. Johnson, read him an e-mail.

"Specialist Johnson's Purple Heart was just approved," said the

e-mail from Johnson's commanding officer, Capt. Jason Ridgeway. "Specialist Johnson has also been recommended for an award for valor."

It took nearly three minutes before a smile swept across Johnson's stern face.

"This makes it all worthwhile," he said.

Inspired by 'Patton'

As of July 3, 718 Purple Heart medals had been awarded to Army soldiers who served in Operation Iraqi Freedom, according to the latest information available from the Military Awards Branch. The award is given to soldiers injured in combat.

Created by George Washington in 1782 as the Badge of Military Merit, the Purple Heart is the oldest military decoration in the world that continues to be used. Some veterans even get license plates that boast of the honor.

Capt. Ridgeway of Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion, 503rd Infantry Regiment wrote of Johnson's bravery in a letter to Johnson's parents.

"(Johnson's) actions ... on the morning of 9 June, 2003, near Al-Samara, Iraq, are a perfect example of the courage and grit that has always been associated with the American paratrooper," Ridgeway wrote. "His fellow soldiers and I could not be prouder of him."

From the time he watched the World War II movie "Patton" at age 12, Johnson wanted to join the military and fight for his country. He was inspired by Gen. George Patton, who in the opening monologue growls, "All real Americans love the sting of battle." But the pivotal scene that inspired Johnson was when Patton walks through a field of dead, maimed soldiers and comes upon the lone man alive, who after a night and morning of battle conquered the last of the enemy in hand-to-hand combat. Patton kisses the American soldier on the forehead.

"That always gets me," Johnson said.

Johnson didn't want a military career, just four years of challenge and adventure. But he got distracted.

In high school, he was known for mischief, like breaking into Newbury Park High to play games on the computers. In college, he was unfocused, but in his junior year, at age 25, Johnson unexpectedly had a daughter named Haileigh.

"I thought, 'Look, it's time to stop partying ... it's not just me anymore,' " he said.

Johnson dropped out of the University North Carolina at Wilmington and joined the Army.

"I wanted a chance to prove myself," he said. "I wanted a chance to prove myself to my country."

Operation Peninsula Strike

As part of the 2nd Battalion, 503rd Infantry, 173rd Airborne Brigade, Johnson arrived in Iraq in late March.

The battalion secured a small abandoned airport in Harir, in northern Iraq about 45 miles northeast of the Kurdish city of Irbil. From there, it made its way to Kirkuk, where it set up operations. Its job was to quell violence between Arabs and Kurds.

The Kurds "were kicking the Arabs out," Johnson said. "There's a major oil field there, and the Arabs came down when Saddam went in. After he left, the Kurds came back and said, 'We used to live here, and get out.' And they used guns to do it.

"You feel bad for these families that got kicked out 20 years ago, but we went with the paperwork."

In June, Johnson heard there was going to be a major operation: Operation Peninsula Strike. He begged to go along.

The convoy of more than 100 vehicles set out after dark June 8 for northern Baghdad to capture Ali Hassan al-Majid, known as "Chemical Ali," and other leading Baath party members. Johnson was in the second vehicle of the convoy, a Humvee with two people in front and three in back. Spc. Tamer Hassanien, 25, of Gainesville, Fla., was driving. In front of them was a cream-colored Toyota truck driven by Army scouts.

The convoy had passed the first checkpoint, and Johnson, who was in charge of communications, radioed that they were approaching the second. Bullets started flying in front of the truck, Hassanien said.

"The lieutenant beside me said, 'Stop,' " Hassanien said in a phone interview from Washington, D.C., where he is recovering. "No more than two seconds later, I got shot in my arm. It came through the front windshield."

Four soldiers were hit. All Hassanien could think about was getting out of the vehicle, which seemed to be attracting all the fire. They were rained upon from two sides. Bullets seemed aimed at his head.

"I remember when I was getting out of the vehicle, (Johnson) was returning fire from the back," Hassanien said. "They were getting hit pretty bad. It was just three guys, and the bullets were pretty accurate."

The Humvee continued to roll. The soldiers had to get out.

"The guy on my left was trying, but he got shot in the face and he was balled up," Johnson said. "I had to snap him out of it. I threw my weapon down and shook him. He just kind of snapped out of it and jumped out of it and ran for the vehicle behind us."

As he jumped from the back of the Humvee, Johnson saw his wrist. Shattered bone poked out of the skin.

"I said to myself, 'This is going to frigging hurt,' " he said.

He used the truck for cover as he continued to shoot and the others got to the next Humvee. Johnson tossed in his gun, jumped in and pulled in the soldier who had been shot in the face.

About 10 minutes later, the shooting was over. Johnson and the other injured soldiers were laid out on the ground, and medics rushed to them.

"While being treated for his wounds, Specialist Johnson talked not of himself or his wounds, but of making sure that his equipment was secure and that the mission be accomplished," his commanding officer wrote.

Investigative runaround

None of the injuries were life-threatening, according to an Army public affairs release issued June 18. The soldier hit in the face was treated and released back to the company. Hassanien and Johnson were airlifted to an army field hospital, eventually ending up at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. That's when they were told by a hospital liaison officer that they weren't getting a Purple Heart. He couldn't give them a reason why.

"I felt pretty bad," Hassanien said. "It felt like something was taken from me -- something I deserved.

"It's a pride thing ... recognition for something I've done."

Johnson's father understood. While his son was in the hospital, the Verizon human resources specialist wrote to senators, congressmen and the Ventura County Star.

The Star contacted elected officials, Army officers at Johnson's base in Vicenza, Italy, and Iraq, as well as an analyst at the Army's awards division. The analyst said it usually takes only a few days to get a Purple Heart after a completed investigation is submitted. There was an incident report but no complete investigation turned in on Johnson's case, analyst Janet Tonnar said Wednesday.

Tonnar said the Purple Heart is awarded even if a soldier is injured by friendly fire, as long as it is in "the heat of battle."

"His incident is still under investigation," she said. "If he has documentation to clarify the investigation, he needs to submit it through the chain of command."

Yet an investigator told Johnson more than a month ago that the investigation was complete.

Although Johnson was troubled by the lack of recognition, when he was released from the hospital last week he knew he still had a mission -- something more important than worrying about the medal he didn't get.

"Being shot reminded me of things I need to get done," he said.

Vindication and relief

He first went to see his mother and daughter in North Carolina. He was joined by his girlfriend, Elena Masara, 23, of Vicenza, Italy, whom he met two years ago.

Tuesday, the couple flew to Newbury Park. There, the most important thing was seeing his 15-year-old brother, Shawn, in football practice.

As his little brother ran wind sprints, Johnson rolled up his sleeve to show his stepmother, Laurie Johnson, his injuries. Thick, pink ridges of scar tissue ran up and down his arm. His stepmother took a step back and gasped, "Oh my God."

Johnson is getting laser treatment to lessen the scarring and physical therapy to help him use his hand again. He has to go back to the hospital Sept. 15.

"It feels like it's asleep all the time," Johnson said. "I'm tired of hugging people with just one arm, if you know what I mean."

Thursday, he took Masara to Venice Beach.

"When I got off the plane, I knew this was where I wanted to stay," Johnson said. "Hopefully, she'll come out here with me. Then I guess I'll have to marry her."

The same day, Johnson's commander e-mailed The Star about the award. Throwing his chest out, Johnson's father read him the note the next morning.

Johnson said he was relieved. "I was so afraid I got shot for nothing."

"People keep asking me, 'Would you do it again?' and it was hard to say yes without recognition."

Some questions about the battle may never be answered. He doesn't know if he was shot by Americans or Iraqis, although one of the bullets remains in his shoulder. He'll never know for sure what held up his decoration. Johnson's commander said Hassanien's Purple Heart is still pending, as is Johnson's medal for valor.

But Johnson is satisfied. He believes if Patton had come upon him after the battle, he would have gotten a kiss on the forehead, too.

With his four years of service up in November, Johnson plans to get a job in civilian communications in Southern California. He's proved what he needed to prove, to himself and his daughter.

"When my daughter and maybe grandchildren pull out my uniform from the attic, I want them to see all the medals and all my achievements," Johnson said. "It will show them that their father and grandfather was a hero for this country."