At some point during the night, a group of armed Kurds stormed into Mohammad Hamady’s home to force him and his family out. During the argument Hamady reached for a glass of water, the Kurds fired a burst of AK47 fire at his feet to punctuate their point, there would be no more debate, and there was no more time, not even for a drink of water.

Hamady wasn’t alone that night; all across his village Kurds were forcing Arabs from their homes at gunpoint.

Forced evictions, a crime normally committed by Kurds against Arabs, are not at all uncommon in these small villages. They happen at night, they happen at gunpoint and, so far, they’ve happened without anyone dying in the process.

But that may only be a matter of time.

The ride out to Hamady’s village is uneventful but filled with reminders of war, poverty and oppression. Almost everywhere around this city of 1.3 million, reminders fill the scenery.

Alongside the road, metal skeletons of giant beasts, once trucks and cars, now lay stripped of tires, doors, carpets—anything that could be useful. Burned out Iraqi tanks and armored personnel carriers lay where they were either destroyed in the fighting or where their crews simply fled. Beyond those, in almost any direction, are innumerable foxholes and artillery positions, sometimes with artillery pieces still intact.

War produces graffiti as well, graffiti in surprising quantities. Some of it has purpose, MAV 2003, painted in Arabic and English on a wall, indicates that the Mine Advisory Group has visited. The majority of the graffiti is political in nature--proclaiming this corner or that street or this block the territory of one of a dozen different parties that is trying to influence this fragile nation. PDK, PUK, both political parties, are scrawled everywhere. Here and there “Boosh” or “Blare” and the occasional “USA” can be found.

|

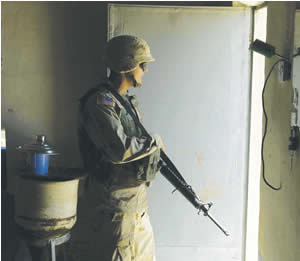

| A soldier assigned to the

319th Field Artillery Regiment (Airborne) stands guards as

First Sgt. James Michelle searches for illegal weapons. Weapons,

typically AK-47 assault rifles, are sometimes confiscated in large

numbers during these searches. |

It’s a sad backdrop but it sheds light on what happened to Hamady’s family that fateful night. In a society so accustomed to violence and terror, an armed group of men forcing a family from a home does not seem out of place. Americans often point to violence on television as a root of violence on the street. But here, in these small villages where there is no TV, there is violence on a scale most Americans could not imagine. If ‘an armed society is a polite society’ as author Robert Heinlein said, then maybe the Kurds wiped their feet before forcing their way into Hamady’s home.

Hamady’s village is as poor as the ones surrounding it. It is not any cleaner or any better kept. It is however, at noon on a Saturday, almost completely deserted.

A lone guard meets the convoy carrying Chief Warrant Officer Bill Moore, special operations coordinator for the 173rd Airborne Brigade, and the soldiers of Delta Battery, 319th Field Artillery Regiment (Airborne).

“Initially they [the Arabs] didn’t want to say anything to us about what was happening,” Moore said. “The general belief was that we were with the Kurds. Now that see us evicting and arresting Kurds, they see us as being more neutral.”

One would like to attribute the forced evictions to wrong doings by Saddam Hussein and the Ba’ath party. During his reign, his attempt at ‘Arabizing’ the region led to the displacement of many Kurdish families. While that may be true in some cases, Moore says most of the forced evictions he’s dealt with lately are simply criminal acts.

“I hate to use the term criminal, but it’s criminal in nature,” he said. “They’re using the excuse that they were evicted by Saddam and the Ba’ath party. However 95 percent of them, or more, never lived there in the first place. Their logic is ‘this is Kurdish land and I’m taking this house and Arabs cannot live on Kurdish land anymore.’ I deem that criminal. It’s wrong and that’s what we’re trying to stop. ”

Soft-spoken and thin, Moore’s lined, weather-beaten face draws a curious contrast to his intense light-blue eyes. You get the impression that he’s the kind of soldier who doesn’t wear all his badges. You also get the impression that he doesn’t need to.

In 85 to 90 percent of the cases, Moore and his team wind up reinstating the home’s original owners.

“I don’t want it to sound like we’re siding with the Arabs. That’s not true,” Moore says. “We’re siding with the Iraqi people.”

Outside a small one-room adobe house, Moore talks to guards with the help of a translator--although the conversation is a bit one-sided. He listens to their side of the story but the result is simple. Leave the village in four days time or else.

|

| Chief Warrant Officer

Bill Moore, special operations coordinator for the 173d Airborne

Brigade, drinks tea with local villagers during a meeting to discuss

the village’s security. Moore, and the soldiers of Delta Battery, 319th

Field Artillery, are working with the residents to help prevent forced

evictions. |

Inside First Sgt. James Michelle, D Battery, 319th Field Artillery (Airborne) searches for weapons. There are always weapons. In every house on every block on every street and in every Iraqi city there are weapons. This time is no exception, an AK-47 assault rifle with several clips of ammunition are confiscated. A wooden rocket propelled grenade and a not-so-wooden rocket propelled grenade are also taken from the house.

Michelle’s soldiers may soon become the de facto police for many of these small villages, at least until the local police, woefully under equipped, under trained and under paid, can take over. It’s a process that could take a while.

“Right now we’re responsible for guarding the oil facility near here,” Michelle said. “We have been doing presence patrols in these villages. It seems to be settling down actually, according to Chief (Moore) it was a lot worse.”

Michelle thinks that the presence of his soldiers will go a long way toward helping the situation.

“Just the unpredictability of when we’ll show up will help,” he said. “And when we do show up talking to the village elders and reassuring them that we are here and our goal is to try and reduce the number of people being evicted from their homes will help.”

“These people want to be reassured—from us—that we’re going to try to help keep them secure. I just going to tell my soldiers to continue to be cautious, to watch for weapons and to watch for danger, but to also be friendly.”

A veteran of the first Gulf War, Michelle explains that, although he understands why Saddam was not removed from power the first time, he’s very happy he’s a part of the process now.

“This time, hopefully, it ends with a society that accepts each other. A society that can join the world’s economy,” he said. “Hopefully, Iraq will become an Arab leader in democracy, there’s a great chance here for them to become leaders in this part of the world in regards to democracy, without fear of extremist or fanatics.”

Eventually it’s hoped that there will be a system in place to solve these disputes. A court or a panel or some arm of the Iraqi government that will help. But it’s a long ways off admits Moore, and everyone knows it.

“I think initially everyone had faith that there will be a system in place down the road that will help,” he said. “However, they are not seeing much progress on it and some have expressed the opinion that it will never be settled in the courts. It’s thousands and thousand of cases, if they wait for the courts it will take 20 years for them to get their homes back. It’s probably true, we’re going to have to look at another system.”