|

| Ali Akbar, 80, a Turkman, left, Ahmed Hussaine, 70, who is Kurdish, center, and Rahman Ali, 76, an Arab, sharing afternoon tea. David P. Gilkey, Detroit Free Press. |

|

| Ali Akbar, 80, a Turkman, left, Ahmed Hussaine, 70, who is Kurdish, center, and Rahman Ali, 76, an Arab, sharing afternoon tea. David P. Gilkey, Detroit Free Press. |

|

| Lt. Anwar Ahmed, left, gets a pat on the back from Lt. Col. Dominic Caraccilo, right, a batllion comander with the 173rd Airborne Brigade. David P. Gilkey, Detroit Free Press. |

|

| Lt. Col. Dominic Caraccilo with 173rd Airborne Brigade yells at his soldiers to get ready to go. David P. Gilkey, Detroit Free Press. |

|

| 1st Lt. Justin Daubert, left, and Staff Sgt. Joel Fehl, right, with the 173rd Airborne Brigade sit down to dinner. David P. Gilkey, Detroit Free Press. |

|

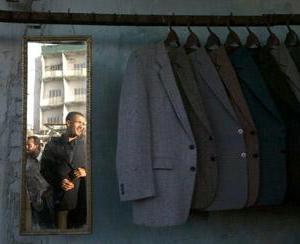

| li Hussun, an ethnic Arab from Kirkuk, try on a suit jacket in the main shopping market in the northern city of Kirkuk. David P. Gilkey, Detroit Free Press. |

|

| A boy watches the traffic pass by near the main shopping market in the northern city of Kirkuk, Iraq. David P. Gilkey, Detroit Free Press. |

|

| Sgt. Monte Massey, 173rd Airborne Brigade, holds 12-year-old Ahmed Ali upside down after he got in the way of a soccer match. David P. Gilkey, Detroit Free Press. | |

KIRKUK, Iraq - When they realized that the newly trained local police force desperately needed walkie-talkies, U.S. troops who patrol Iraq's fourth-largest city didn't wait for the civilian bureaucracy to buy them, as have their counterparts in Baghdad.

The soldiers in Kirkuk found a dealer and ordered the police radios with their emergency funds. They did the same with weapons, vehicles and office furniture.

Today, while many once-looted Baghdad police stations remain sparsely furnished shells, the ones in Kirkuk, which also were gutted, are freshly painted and sparkling with renovations - including air conditioners, exercise equipment and cafeterias. And while police in the capital are still struggling with shortages, Kirkuk's police force is among the best equipped in the country.

"Security was our top priority, so we couldn't wait," said Col. William Mayville, commander of the 173rd Airborne Brigade, the main ground force in Kirkuk. "We're a couple of chapters ahead of the rest of Iraq on a lot of this stuff."

Kirkuk, a multi-ethnic city of Kurds, Arabs, Turkmen and Assyrians that is 150 miles north of the capital, may be the U.S. military's greatest Iraq success story. Attacks on soldiers are rare, violent-crime rates are low, and Iraqis have worked with Americans to restore basic services to pre-war levels.

In fact, a close look at Kirkuk suggests that the occupation strategy could have been used to avoid problems encountered elsewhere in the country.

The paratroopers in Kirkuk, like those in Mosul, the other major city in the north, have thrown themselves into nation-building, and they've outpaced the rest of Iraq in turning over local government, security and reconstruction tasks to Iraqis.

That effort is aided by the peaceful environment, partly a result of the city's geography and ethnic balance, and the 173rd Airborne's quick moves to establish control after the war. Another big factor is that there's less coalition bureaucracy; soldiers can act on the spot to solve problems.

In Kirkuk, a city of 1 million people, the brigade of about 3,000 soldiers is the sole military presence, compared with about 37,000 troops in Baghdad, population 5 million. The 173rd parachuted into northern Iraq in March and were fixing things for a month before L. Paul Bremer, Iraq's top administrator, or Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, the military commander, set foot in the country.

Although it provides money, Bremer's Baghdad-based Coalition Provisional Authority has no U.S. staff in the city. And unlike every other brigade commander in Iraq, Mayville doesn't really work for a general, because the Vicenza, Italy-based 173rd is not part of a division. (It is "attached" to the 4th Infantry Division, which has its hands full in Tikrit, Saddam Hussein's hometown.)

That unique autonomy has allowed Mayville and his senior commanders to work their will on every aspect of civic life, including politics, infrastructure, education and trash collection.

"Sometimes it seems like the (civilian authority in Baghdad) is looking for something that fits into their 30-year plan," said Maj. Andy Rohling, a battalion operations officer. "We're looking for something that will fix the problem right away."

One team of soldiers helped form a multi-ethnic local government, headed by a Kurdish mayor with Arab and Turkomen deputies who were elected by 300 community leaders. Another team is tackling water, sewer, electricity and economic development projects. Both groups work each day in Kirkuk's government center, where they are vastly outnumbered by Iraqi employees.

"Each one of my guys is matched up with a local government official," said Maj. Brian Maddox, a tank officer who heads up what the brigade calls Task Force Civil. "Our motto around here is to put an Iraqi between us and the problem."

The only parallel in Iraq is nearby Mosul, another multi-ethnic northern city, where the 101st Airborne Division has used a similar approach with good results. The northern cities of Irbil and Sulaymaniyah are also doing well, but that's less surprising since those are part of the Kurdish enclave that was kept out of Saddam Hussein's reach after the 1991 Gulf War by a U.S.-enforced no-fly zone.

The biggest threat to stability in Kirkuk is tensions among the ethnic groups, which the soldiers spend their days trying to diffuse. Sometimes the tensions flare into violence, as on May 17th when soldiers say they shot and killed more than a dozen armed Arab rioters. Most recently, the 173rd has begun a campaign to establish ethnic balance on the police force and to force Kurds to stop flying the Kurdistan flag on public buildings.

Those actions drew protests, but Kirkuk remains one of the few places in Iraq where questions about American soldiers draw mainly positive responses from people, including from Arabs who are more predisposed than Kurds or Turkomen to dislike the American occupation.

"They are dealing with people in a good way," said Fatah Mohammed, 47, an unemployed Arab.

"We love the Americans here," said Mustafa Adna, 18, a Turkmen fruit vendor. "They have done many good things. Kirkuk is a stable city."

To be sure, there are many factors that have made Kirkuk more hospitable to U.S. troops than Baghdad and other cities in the so-called Sunni triangle. Although the city is 40 percent Arab, the rest of the population is made up of ethnic groups who were oppressed by Saddam and pre-disposed to see U.S. forces as liberators.

Even Kirkuk's Arabs felt neglected by the old regime, so residents have a stake in the new order. Kirkuk is home to one of Iraq's two state-owned oil companies, which means its residents include a large number of well-educated bureaucrats. And the city fell with scarcely a shot fired after its Iraqi army defenders melted away.

The 173rd, which had parachuted into a northern valley weeks before, entered the city April 11. Within two weeks, they had restored some electricity and water service to most of the city. By contrast, the 3rd Infantry Division was still mopping up resistance in Baghdad well into May, and it eventually left, replaced by the 1st Armored Division.

To establish order in Kirkuk, the 173rd immediately kicked out the Kurdish militias that had streamed in and began a concerted campaign to rid the city of weapons. They seized them at traffic checkpoints and conducted a series of raids.

Yet even as they were hunting enemies, commanders in Kirkuk also did something unheard of in most of the rest of Iraq: They assigned soldiers to live in residential houses in the city. Three rifle companies of paratroopers live in former Baathist-owned mansions.

The houses are fortified with sandbags and concertina wire, but they are within shouting distance of neighbors, who regularly bring meals. At Chosen Company's house the other day, soldiers played an Iraqi police team in a soccer game (the Iraqis won, 1-0) and then hosted a barbecue.

Although only one 173rd soldier has been killed in action, the brigade has seen its share of hostilities, in part because it also patrols Sunni Arab towns south of Kirkuk. Just last week, a convoy was attacked by rocket-propelled grenades, and the attackers were killed.

Still, soldiers of the 173rd regularly eat and shop in local establishments and interact with residents. By contrast, for example, the 82nd Airborne battalion based in Mahmudiya, south of Baghdad, doesn't allow its troops to buy so much as a can of soda outside their walled and heavily guarded compound off a major highway.

The 173rd's approach is riskier. The houses have been attacked occasionally with rocket-propelled grenades, and one soldier lost his legs in such an attack. But the risk brings rewards, said Lt. Col. Dominic Caraccilo, who commands the 2nd Battalion, 503rd Infantry, which lives in the city. Soldiers know their neighborhoods intimately and regularly get good tips about potential problems.

On Monday, one such tip led to the arrest of some weapons dealers.

"I just don't understand how you could hold yourself out as doing nation-building and not live among the people," Caraccilo said.